For help, advice and telephone ordering call our team on 0121 666 6646

Are you sure you wish to delete this basket?()

This action cannot be undone.

Sorry, something went wrong

Please report the problem here.

Candy Gourlay on the unknown colonial history behind Bone Talk and Wild Song

April 5th 2023

|

About Candy Gourlay Candy Gourlay was born in the Philippines and grew up under a dictatorship. As a child, she wondered why books only featured pink-skinned children who lived in worlds that didn’t resemble her tropical home in Manila. It took her years to learn that Filipino stories also belong in the pages of books. She has been shortlisted for many prizes, including the Waterstones and Blue Peter Prize (Tall Story), Guardian Prize (Shine) and the Costa and Carnegie (Bone Talk). |

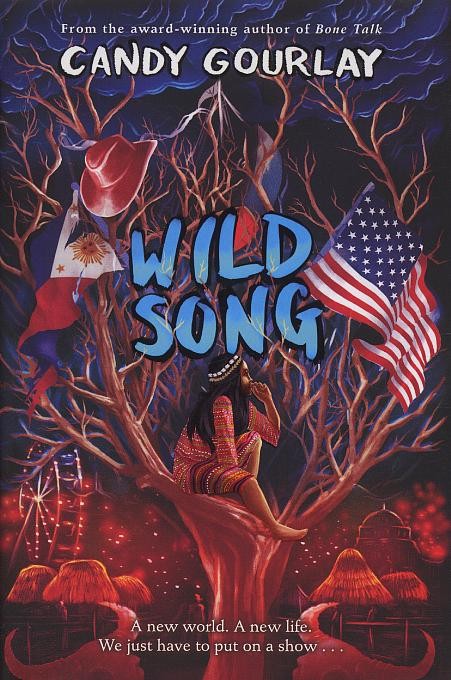

Following on from her acclaimed title, Bone Talk, the new Wild Song novel from Candy Gourlay reunites readers with the character of Luki, an Igorot girl from the Cordillera central mountain range of the Philippines. Reflecting the indigenous Filipino experience in the 20th century, this startling teen book is a journey over two decades in the making. In our guest blog, Candy reveals the historical research that inspired the books, and how she explored discrimination and prejudice to capture the dark American colonial history that forms their backdrop.

The century-old photo that inspired meI knew from the beginning that writing Wild Song would be an enormous, life-changing experience. I have been working on it on and off since 2005, when I first stumbled on a most peculiar photograph. It was of a boy dancing hand and hand with a woman [pictured]. The boy, it was immediately obvious to me, was from an indigenous Filipino people called the Igorots. But the woman! Her dress bore the silhouette of the Edwardian era: high-necked, pigeon-shaped, waist tightly tucked in by a corset. It was a segregated era, when people of colour were not allowed to share space with white people, except as servants. It was a puritanical time, when wives didn’t hold hands in public with their husbands. And yet here she was holding hands with a boy…and not just any boy, a scantily clad, brown boy. A spectacular setting: the 1904 St. Louis World’s FairWhen I learned that the photo had been taken at the 1904 World’s Fair in St Louis, Missouri, I wondered why I had never seen it before. Surely such an iconic image taken at such a massive event, would have been mentioned by my history teachers when I was growing up in the Philippines? Reading up on the fair, I began to feel that familiar tingle of discovering a story that I wanted to write. What an incredible setting! A city of white palaces, sparkling lagoons, waterfalls and parks had been built in what had once been a forest. The pinnacle of technology was on display: flying machines, a Ferris wheel, automobiles, the telegraph machine, the X-ray, electric lights, the baby incubator. Fabulous acts were on rotation: a wild west show, exotic dancers from the Middle East, wild animals, acrobats. And from all over the globe, indigenous folk showcasing their diverse cultures. |

|

|

The “dark heart” of my research

But it is a fact little known, especially to contemporary Americans, that the United States invaded the Philippines in 1899. Even we Filipinos do not dwell on this history. Nobody wants to remember a brutal war. Nobody wants to remember that we were the losers. Researching 1904, I couldn’t escape the Philippine American War that had officially ended just a year before, even though it unofficially carried on for several years. I realised that the Filipinos who had been taken to the World’s Fair were practically war trophies.

Over years of research, I discovered even more sinister facts. The anthropologist who recruited the Igorots? He was a firm believer in eugenics, the racial “science” that believed people of colour were doomed to extinction and that scientists should pursue the development of a “perfect” (meaning white) race. Much of the World’s Fair had been designed as an anthropological experiment, that the indigenous people were measured and tested. There were graphics that diagrammed the evolution of man, with white Americans on top, and Filipino indigenous people at the bottom.

I learned that the setting of this novel I was itching to write had a very, very dark heart. And I knew I was not ready to write it. I needed to understand many things. Not the least of which was to see beyond the racist depictions of Igorots both in newspaper and anthropological texts, to see them as human beings. So I stopped writing Wild Song and wrote another book: Bone Talk.

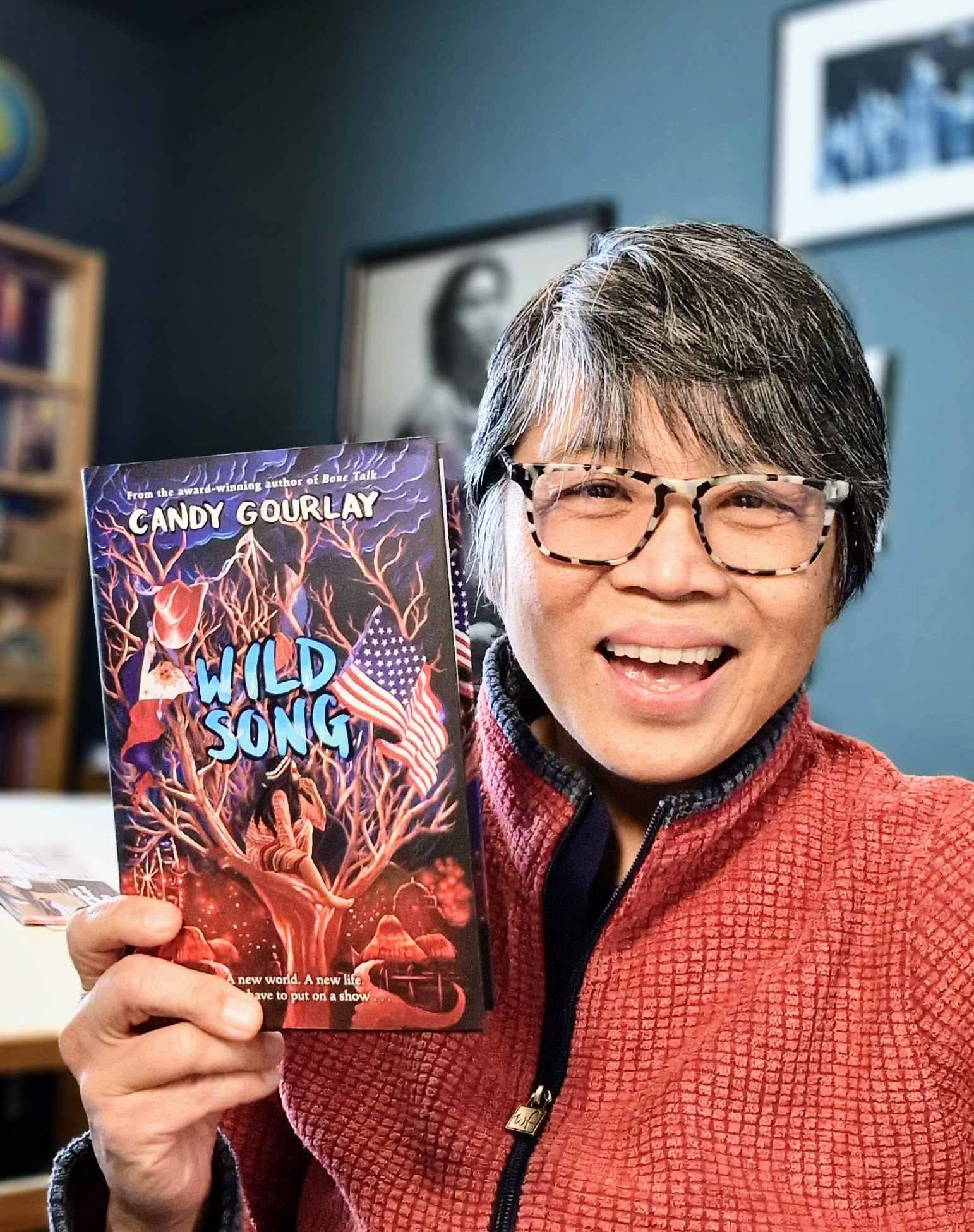

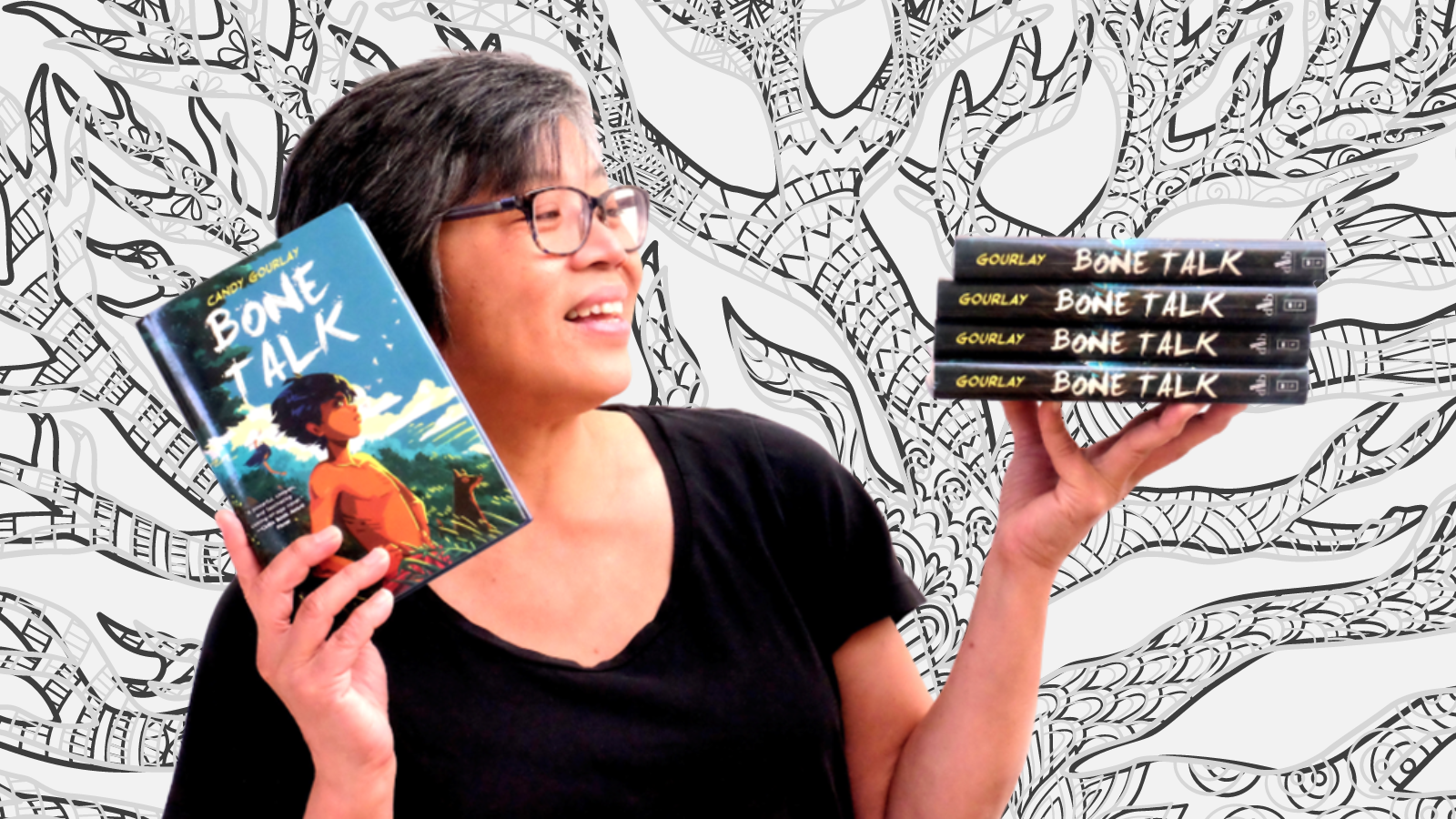

Candy wrote Bone Talk in response to the American invasion of the Philippines, before returning to Wild Song (Photo credit: Mia Gourlay, 2019)

Candy wrote Bone Talk in response to the American invasion of the Philippines, before returning to Wild Song (Photo credit: Mia Gourlay, 2019)

Developing the story

It is said that any act of creativity begins with a question. With Bone Talk, my question was this: what would happen if a boy knew nothing about the outside world and then the outside world came to him? It is 1899. 10-year-old Samkad and his best friend, Little Luki, play and squabble and dream of becoming warriors, even though Little Luki is a girl and their village had never seen a woman become warrior before. And then a war begins in the lowlands and strange foreign men called ‘Americans’ come to their village.

Wild Song is set five years later; Samkad and Luki are now considered grown-ups. It is 1904, the Americans now rule the Philippines. But although they have changed many things, some things have not changed at all. Girls must work in the paddy fields, not hunt in the night, which Luki does in secret. And girls must marry, when told to do so. It is the last straw. And Luki accepts an invitation to visit the World’s Fair in America, thinking she had everything to gain and nothing to lose.

The question that set me on my journey for Wild Song was this: what does it mean to be civilised? The Americans of yesteryear looked at the Igorots and believed they were primitive people who needed civilising. But, after all these many years of researching and learning how to write Wild Song, I knew the answer to my story’s question: to be civilised is to see the humanity of those who are not like you.

|

Wild SongA follow-up to Bone Talk, this teen title is set in 1904. Luki has lived a tribal life in the mountains of the Philippines. Now she's growing up, she is expected to become a wife and a mother, but Luki isn't ready to give up her dream to become a warrior. When her tribe are offered a journey to America to be part of the St. Louis World's Fair, Luki will discover that the land of opportunity does not share its possibilities equally. We recommend this title as useful topic support around colonialism and USA history. |

📚 READ NEXT: ALAKE PILGRIM TALKS DIVERSITY, MONSTERS AND CARIBBEAN INFLUENCES